Let’s crawl the Web! It will be fun!

Not your legal department

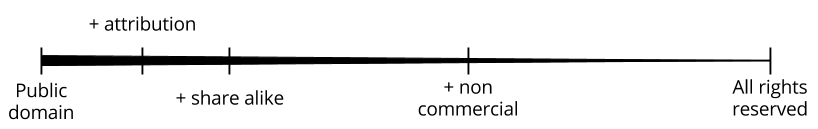

The foremost condition before a dataset can be called “open”, is that anyone is legally allowed to use it for any purpose. A public license gives anyone more rights on this datasets. Many exist and some organizations might even decide to create their own license. Which license should you use for your data? Let’s ask the Twitterverse first…

What’s the best license/waiver for #opendata? The goal should be to maximize the reuse of the dataset, such as with public transit schedules

— Pieter Colpaert (@pietercolpaert) 2017, February 7

Intellectual Property

As Intellectual Property Rights (ipr) legislation diverges across the world, we only checked the correctness of this chapter with European copyright legislation [4] in mind. When a document is published on the Web, all rights are reserved by default until 70 years after the death of the last author. When these documents are reused, modified and/or shared, the conscent of the copyright holder is needed. This conscent can be given through a written statement, but can also be given to everyone at once through a public license. In order to mark your own work for reuse, licenses, such as the Creative Commons licenses, exist, that can be reused without having to invent the same legal texts over and over again.

Copyright is only applicable on the container that is used for exchanging the data.

On the abstract concept of facts or data, copyright legislation does not apply.

The European directive on sui generis database law [5] specifies that, however, databases can be partially protected, if the owner can show that there has been qualitatively and/or quantitatively a substantial investment in either the obtaining, verification or presentation of the contents of the database

[6].

It allows a database owner to protect its database from (partial) replication by third parties.

So, while there is no copyright applicable on data itself, database rights may still be in place to protect a data source.

In 2013-2014, the Creative Commons licenses were extended to also contain legal text on the sui generis database law, and would since then also work for datasets.

More information on the definition of Open Data maintained by Open Knowledge International is available at opendefinition.org [7]

Data can only be called Open Data, when anyone is able to freely access, use, modify, and share for any purpose (subject, at most, to requirements that preserve provenance and openness)

.

Some data are by definition open, as they there is no Intellectual Property Rights (ipr) applicable.

When there is some kind of ipr on the data, an open license is required.

This license must allow the right to reuse, modify and share without exception.

From the moment there are custom restrictions (other than preserving provenance or openness), it cannot be called “open”.

Uncertainty

For this text, I’ve consulted The Jurists, who were so kind to give me their opinion on this matter. While the examples given here may sound straightforward, these two ipr frameworks are the source of much uncertainty. Take for example the case of the Diary of Anne Frank [8], for which it is unclear who last wrote the book. While some argue it is in the public domain, the organization now holding the copyright states the father did editorial changes, and the father of Anne Frank died much later. For the reason of avoiding complexity when reusing documents – and not only for this reason – it is desired that the authoritative source can verify the document’s provenance or authors at all time, and a license our waiver are included in the dataset’s metadata.

When this book would be processed for the data facts that are stored within this book, what happens to copyright? Rulings in court help us to understand how this should be interpreted. A case in the online newspaper sector, Public Relations Consultants Association Ltd vs. The Newspaper Licensing Agency Ltd [9] in the UK in 2014, interpreted the 5th article of the European directive on copyright in the way that a copy that happens for the purpose of text and data mining is incidental, and no conscent should be granted for this type of copies.

Next, considering the database rights, it is unclear what a substantial investment is, regarding the data contained within these documents. One of the most prominent arrests for the area of Open (Transport) Data, was the ruling of the British Horseracing Board Ltd and Others vs. William Hill Organization Ltd [10], which stated that the results of horse races collected by a third party was not infringing the database rights of the horse race organizer. The horse race organizer does not invest in the database, as the results are a natural consequence of holding horse races. In the same way, we argue the railway schedules of a public transport agency are not protected by database law either, as a public transport agency does not have to invest in maintaining this dataset. These interpretations of copyright and sui generis are also confirmed by a study of EU Commission on intellectual property rights for text mining and data analysis [6].

Which licenses to use?

When I’m talking about Open Data, I’m talking about data for which the reuse should be maximized. And it’s my responsibility to make sure that my data interface can handle peaks of high demand. I want user agents – or crawlers, bots and scrapers – of any kind to retrieve my data and process it.

Talking about copyright within this Web context becomes difficult as the value of the container the data is contained in is marginal to the data itself. Almost all “copies” on the Web are merely incidental, thanks to the great caching mechanism behind the HTTP protocol. It is thus questionable how applicable existing copyright legislation is on the documents when publishing data in a technically interoperable way on the Web.

When we want the data facts itself to be reused as broadly as possible, we do not want to make it unnecessarily complex for data consumers. The document that ships our data is automatically copyrighted, so we want to waive this copyright. Furthermore, when we would be able to protect our data through sui generis, it should be clear we don’t want to do that. For this purpose, the Creative Commons Zero waiver is the best “license” to use: it waives, to the extent possible, your IPR from a document and it indicates that you do not have the intention to enforce any remaining intellectual property rights that would exist.

Attribution

Using an Attribution license still complies to the Open Definition.Requiring that you mention the source of the dataset in each application that reuses my data, still complies to the Open Definition. There is no need to argue with anyone that uses for example the CC BY license: you will only have the annoying obligation that you have to mention the name in a user interface. This is useful for datasets which are closely tied to their document or database: when for example reusing and republishing a spreadsheet, I can understand you will want that someone attributes you for created that spreadsheet. However, for data on the Web, the borders between data silos are fading and queries are evaluated over plenty of databases. Then requiring that each dataset is mentioned in the user interface is just annoying end-users.

It is however important that the provenance of every kind of question can be looked up. When I see an answer on my screen, I would love to have an “Oh Yeah?” button (coined by Tim Berners-Lee) for, which explains how the question was answered and links me to the original sources. I however do not believe this should be a legal requirement. It is just a design principle I believe future app developers should adopt. Even if it would then not be visible in an end-user app, your browser could still expose this kind of provenance information using e.g., a browser extension.

Although CC0 doesn’t legally require users of the data to cite the source, it does not affect the ethical norms for attribution in scientific and research communities.

Figshare on why they use CC0

Share alike

Using a Share Alike license still complies to the Open Definition. The share alike requirement, as the name implies, requires that when reusing a document, you share the resulting document under the same license. I like the idea for “viral” licenses and the fact that all results from this document will now also become open data. However, what does it mean exactly for an answer that is generated on the basis of 2 or more datasets? And what if one of these datasets would be a private dataset (e.g., a user profile)? It thus would make it even more unnecessarily complex to reuse data, while the goal was to maximize the reuse of our dataset.

Non commercial

Using a Non Commercial license does not comply to the Open Definition.When you want to reuse datasets sustainably, you are going to need a business model, and thus it is a condradictio in terminis that you may be able to reuse data in a non commercial way.

Yes, but…

#opendata. Can real-time transit data really be open? https://t.co/B88PmsRdw2

— noel (@opendataforum_) 2017, February 8

Data services are not data publishing

In “Open Licensing of Real-Time Public Sector Transit Data” [1], Scassa and Diebel argue that the license on top of real-time open data needs to be different than on top of a dataset. While I agree with their analysis that a data service needs different terms than data publishing (read “I do not want your Open Data API, I’d rather scrape your website”), they do not make the distinction. Real-time public transport data, as with Linked Connections or gtfs-rt means that next to the data dump, a file is put online, which is updated each (for example) 30 seconds with the latest delay and cancellations information. Still, this is just a file that can be delivered quickly to an end-user, and falls under the same terms as a data dump.

A route planning API however, something I find a very bad idea for an Open Data strategy (read “Route Planning services should not be built by governmental organizations”), indeed needs its own kind of terms. Even more: a route planning API should not even be publicly available. Concluding that there are various implications with real-time open data for smart cities in general is due to the fact that they looked at the wrong kind of publishing interfaces.

I do not want anyone to pretend they’re me

I got a question from a colleague asking what license he should put on his open dataset of his titles and abstracts of his papers in. When I told him that he should put it in CC0, he asked whether anyone would then be able to take his abstract and republish it as if it were theirs.

Well, plagiarism is a different thing. Today, you can also not take the work of Shakespeare, which is in the public domain, and hand it in as your own homework or paper submission. It is already covered and should thus not be reflected in the license you put on your work. The data of my colleague, who also publishes data about me, is now available under the CC0 conditions.

CC0’s legal interpretation is too fuzzy

On the public forum of the Open Data Institute of Queensland, when the question was asked whether to use CC0 or CC-BY, CC-BY was recommended. The claim is made that CC0 brings more legal uncertainty than CC BY. Also across different European member states, legislation indeed still varies to what extent you can waive your rights on top of data.

While ODI Queensland argues that this legal uncertainty of the exact interpretation is bad, a lot depends on intention as well. Documenting your dataset with a CC0 waiver indicates to potential reusers that the data owners will not enforce unwaived rights. This intention is clear with CC0, while it is not with CC BY, where “how to attribute” diverges across different datasets. As keeping the provenance of your data when answering questions is an important work ethic of a data scientist anyway, I would still accept CC BY as a standard license for Open Data.

With CC0, data owners also waiving their reponsibility?

I got an interesting reaction on the twitter poll saying that waiving the legal obligation to keep your data up to date is not a good practise for Open Data.

@pietercolpaert Creative Commons 0 is not a good license for open data, implies you're abandoning your rights (inc. promise of updates).

— The Data Starter (@TheDataStarter) 2017, February 7

A license or a waiver that states that a dataset comes without waranty, does not give a wildcard for being able to put “alternative facts” in datasets. E.g., when a document you publish is the authoritative source for something, you are responsible, as part of your job description, to correctly represent the real world. Responsibility for a dataset should not be something that depends on an open data license.

The metadata of the file should sketch the context in which the data is being published. Is it a one time file that is published as part of an experiment to open up the first datasets? Or is this an authoritative source than can be relied upon by various Web agents?

Our legal department wants us to draft our own license

Machines already know how to interpret links to licenses like the CC0 or CC-BY license. If you create your own license, how open it may be, this license also needs again to be understood by user agents. The effort that is put in to create a new license, could be better used to annotate your dataset better, so that user agents can automatically be guided to execute the desired behavior.

Conclusion

Copyright legislation varies slightly across different countries world-wide. The biggest building blocks we do share and we can assume copyright is only applicable on documents, not on the data facts itself. In Europe, when you extract data from documents, this is regarded as an “incidental” copy for which the copyright legislation should not be applied. For databases, a “sui generis” protection law exists. This law dictates that you can protect your data when you invested substantially in its creation. For data that are a natural consequence of what you are paid for to do (e.g., lottery results or train schedules), this law does not apply.

While copyright and sui generis for publicly available data on the Web are covered in uncertainty (I call it the gray zone of “ask forgiveness later”), still some reusers want legal certainty. A good waranty on not getting sued over certain data reuse is of course knowing what the intention of the data publisher is. If the data publisher indicates that the data is free to reuse, even when no © or sui generis applies, you can be certain that you are allowed to reuse the dataset.

As a data publisher, you may try to enforce an attribution or share alike license, but on top of data, this becomes really hard to enforce. If you are not going to put in the effort to enforce attribution, which is anyway part of the work ethic of any data scientist, why would you put in the legal obligation anyway? It would only make it more vague what the conditions are to reuse your data, and for Open Data, your foremost goal is to maximize its reuse anyway. Some datasets are made available on the Web using a data service instead of documents. I agree that this needs different terms and conditions to be accepted and maybe even needs authentication before you are allowed to access the service. This is not a proper way to publish data on the Web though. While I would have no big problems with an attribution license on top of the dataset — it’s still open data — I overall recommend the CC0 waiver for datasets published in documents.

References

- [1]

- Scassa, Teresa and Diebel, Alexandra, Open or Closed? Open Licensing of Real-Time Public Sector Transit Data (December 19, 2016). (2016) Journal of e-Democracy 8:2, 1-19; Ottawa Faculty of Law Working Paper No. 2017-02.

- [4]

- European Parliament: “Directive 2001/29/EC of the European Parliament and of the Council of 22 May 2001 on the harmonisation of certain aspects of copyright and related rights in the information society”, eur-lex (2001)

- [5]

- European Parliament: “Directive 96/9/EC of the European Parliament and of the Council of 11 March 1996 on the legal protection of databases”, eur-lex (1996)

- [6]

- J-P. Triaille, J. de Meeûs d’Argenteuil, A. de Francquen: “Study on the legal framework of text and data mining”, (2014)

- [7]

- Open Knowledge International: “The Open Definition”, (2004)

- [8]

- G. Moody: “Copyright chaos: Why isn’t Anne Frank’s diary free now?”, Ars Technica (2016)

- [9]

- Judgment of the Court (Fourth Chamber): “Public Relations Consultants Association Ltd v Newspaper Licensing Agency Ltd and Others.”, eur-lex (2014)

- [10]

- Judgment of the Court (Grand Chamber): “The British Horseracing Board Ltd and Others v William Hill Organization Ltd.”, eur-lex (2004)

- [15]

- Walravens, Nils, M. Van Compernolle, P. Colpaert, P. Mechant, P. Ballon, E. Mannens: “Open Government Data’: based Business Models: a market consultation on the relationship with government in the case of mobility and route-planning applications”, 13th International Joint Conference on e-Business and Telecommunications (2016)

- [16]

- P. Colpaert, M. Van Compernolle, N. Walravens, P. Mechant: “Open Transport Data for maximizing reuse in multimodal route planners: a study in Flanders [DRAFT]”, IET (2017)

- [18]

- R. Verborgh: “get doesn’t change the world”, (2012)

- [19]

- M. Belshe, R. Peon, M. Thomson: “Hypertext Transfer Protocol Version 2 (http/2)”, ietf (2015)

- [21]

- B. Farias Lóscio, C. Burle, N. Calegari: “Data on the Web Best Practices”, (2016)

- [22]

- T. Berners-Lee: “Information Management: A Proposal”, (1989)

- [23]

- R. Verborgh, S. van Hooland, A.S. Cope, S. Chan, E. Mannens, R. Van de Walle: “The Fallacy of the Multi-API Culture: Conceptual and Practical Benefits of Representational State Transfer (rest)”, Journal of Documentation (2015)

- [24]

- R. Fielding: “Architectural Styles and the Design of Network-based Software Architectures”, (2000)

- [25]

- O. Hartig, C. Bizer, J.C. Freytag: “Executing sparql queries over the Web of Linked Data”, Springer Berlin Heidelberg (2009)

- [26]

- R. Verborgh, M. Vander Sande, O. Hartig, J. Van Herwegen, L. De Vocht, B. De Meester, G. Haesendonck, P. Colpaert: “Triple Pattern Fragments: a Low-cost Knowledge Graph Interface for the Web”, (2016)